Part 2 of the MERISE series

New here? Part 1 covers why MERISE exists and how it differs from ER modeling. Short version: it’s a conversation framework that forces business stakeholders to articulate their actual rules before you write a single line of SQL.

Last time, I introduced MERISE and why this French methodology kicks ass for database modeling. Today, we’re diving into the first and most crucial step: the Conceptual Data Model (MCD).

Here’s the thing most DBAs get wrong: they think the MCD is about drawing pretty boxes. It’s not.

The MCD is a conversation tool. It’s how you prevent the 3-year-later disaster: inconsistent data because constraints don’t exist, performance collapse because columns got added ad-hoc, update anomalies because the same data lives in five places.

All of that starts with one bad decision: skipping the conversation and jumping straight to CREATE TABLE.

Why the MCD exists 🔗

Before touching a single line of SQL, you need answers. The MCD gives you a structured way to ask the right questions:

- What exists? (Entities)

- How do things connect? (Relationships)

- What are the rules? (Cardinalities + attributes)

Let’s see this in action with a real example.

As we walk through this zoo example, watch for the red flags I’ll point out at the end - they’re the tells that you need to dig deeper.

The zoo database: a case study 🔗

I’ll use the zoo example from my training. It’s simple enough to understand, complex enough to show where things go wrong.

Step 1: Initial request 🔗

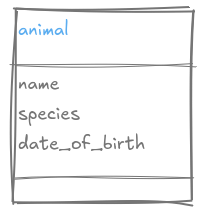

Business says: “We need to track our animals.”

Okay. What’s an animal?

Looks good, right? Wrong. This is where you start asking questions.

Step 2: The species question 🔗

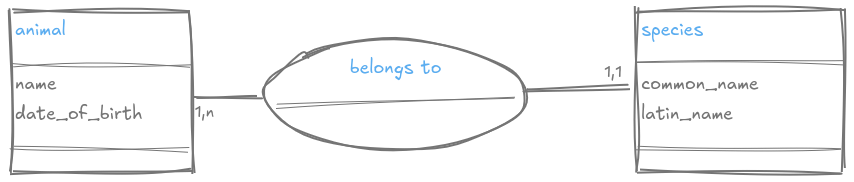

You: “Wait, species is just text? What if two people spell ‘African Elephant’ differently?”

Business: “Oh yeah, species should be standardized. And we need Latin names too.”

Now we have:

Cardinality question: Can an animal belong to multiple species? (No, obviously.) Can a species have multiple animals? (Yes, hopefully.)

This is a one-to-many relationship.1

Step 3: The enclosure question 🔗

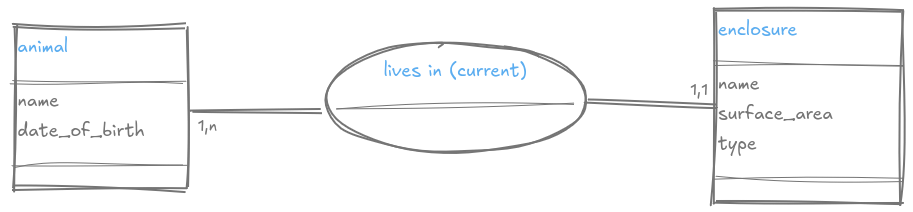

Business: “Animals live in enclosures.”

You: “One animal, one enclosure? Or can animals move around?”

Business: “Well, sometimes we move them for breeding programs…”

Ah. Now it gets interesting.

Cardinality: One animal lives in one enclosure at a time (1,1). One enclosure can house multiple animals (1,n).

But wait - “at a time” is doing heavy lifting here. That’s your clue you might need history tracking later. Note it. Move on.

Step 4: The breeding program 🔗

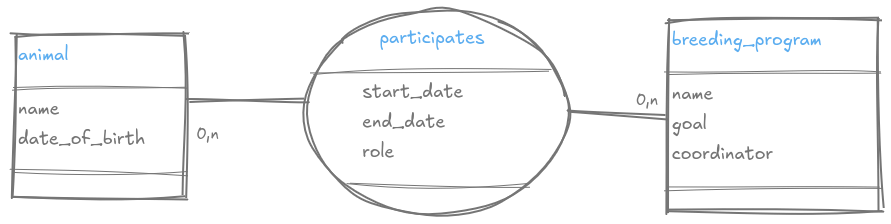

Business: “We need to track breeding programs.”

You: “Okay. What’s a breeding program?”

Business: “It’s when we move animals between zoos for mating.”

You: “So an animal can participate in multiple programs?”

Business: “Yes.”

You: “And a program involves multiple animals?”

Business: “Yes.”

This is a many-to-many relationship:

Notice how the relationship has its own attributes? In MERISE, relationships (ovals) can have attributes, they don’t become entities, yet. This is different from traditional ER modeling where you’d create a junction entity.

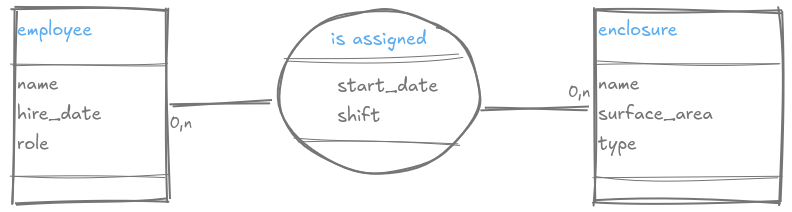

Step 5: The feeding question 🔗

Business: “We need to track feeding schedules.”

You: “Is feeding per animal or per species?”

Business: “Per species. All elephants get the same diet.”

Key insight: You almost modeled this wrong by linking animal to food. The MCD conversation saved you.

Step 6: The employee question 🔗

Business: “Zookeepers need to be assigned to enclosures.”

You: “One keeper per enclosure?”

Business: “No, multiple keepers rotate.”

You: “Can a keeper handle multiple enclosures?”

Business: “Yes.”

You: “And can a keeper exist in the system without being assigned yet?”

Business: *“No.”

You: “What about onboarding, PTO, sick leaves ? Do keepers exist in the system without enclosure assignments in those cases?”

Business: “Oh, good point. Yes, we hire people before assigning them.”

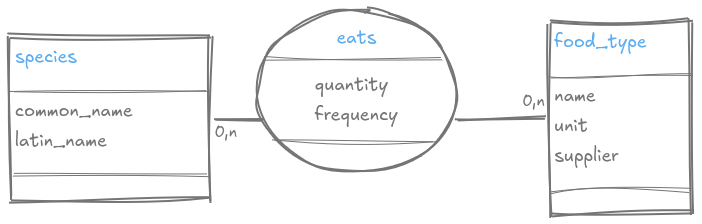

Another many-to-many, with minimum cardinality 0 on the employee side:

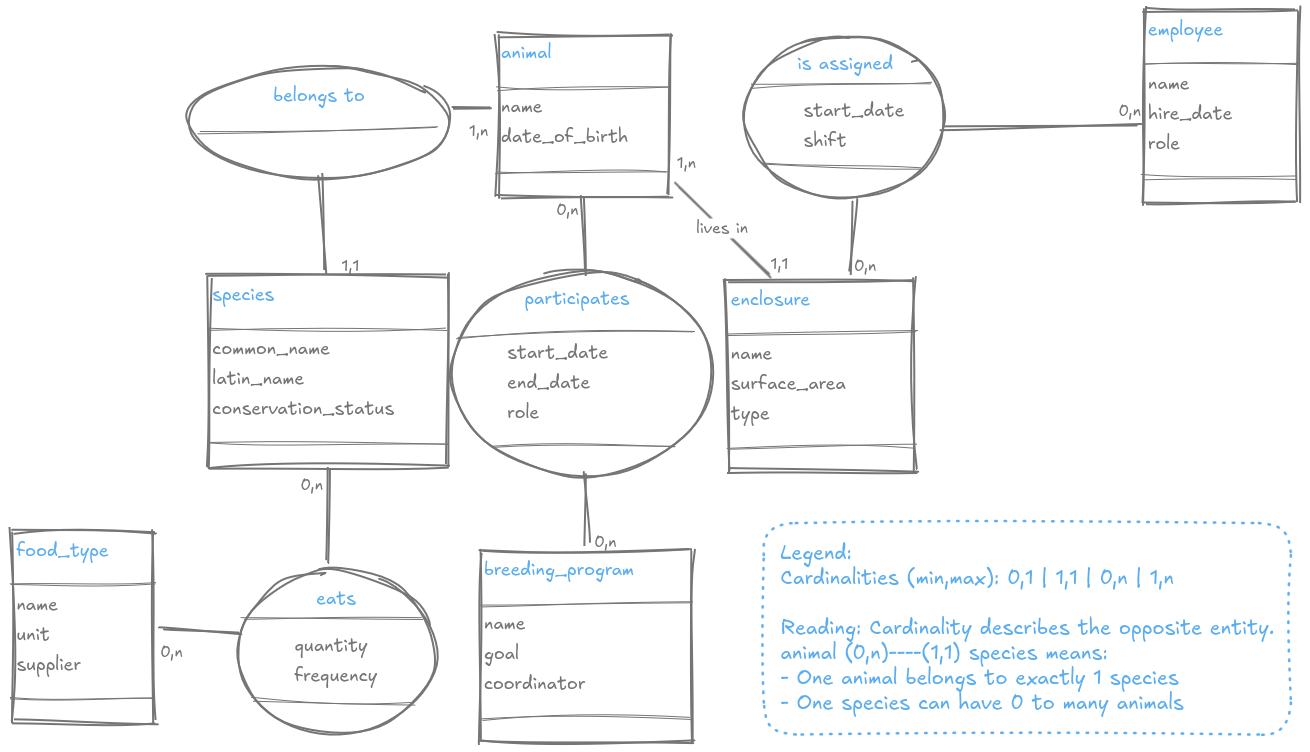

Step 7: The final MCD 🔗

After all these conversations, here’s what we have:

The three magic questions 🔗

Every entity-relationship pair needs these answered:

1. Minimum cardinality 🔗

“Can this exist without the other?”

- Animal without species? No → minimum 1

- Species without animals? Yes (newly added species) → minimum 0

- Enclosure without animals? Yes (new/empty) → minimum 0

2. Maximum cardinality 🔗

“Can this connect to multiple?”

- Animal in multiple enclosures? No → maximum 1

- Enclosure with multiple animals? Yes → maximum n

- Employee assigned to multiple enclosures? Yes → maximum n

3. Relationship attributes 🔗

“Does this connection have its own data?”

- assignment has start_date and shift

- participation has role (donor/receiver)

- Simple links like “belongs to” have no attributes

Red flags during MCD conversations 🔗

These patterns tell you there’s more to explore:

Business says: “Just put everything in one table.” Ask them to walk through a specific example. “Let’s say we add a new animal tomorrow, what information do we need?” Real scenarios expose the hidden complexity.

Business says: “We’ll figure out the details later.” Pick one detail and dig. “Let’s just clarify this one relationship now. It’ll take 5 minutes and save us weeks later.” Start small, build confidence.

Business uses “sometimes”: “Sometimes animals are in two enclosures.” “Interesting! When does that happen? Is it temporary during moves, or something else?” The word “sometimes” hides a business rule you need to capture.

Business can’t answer cardinality: “I don’t know if it’s 0 or 1.” “No problem. Let’s think through scenarios. Can you have a species in the system before any animals arrive? What happens when the last animal of a species dies?” Make it concrete, not abstract.

The goal isn’t to interrogate people. It’s to help them articulate rules they know but haven’t formalized yet.

Why this matters 🔗

By the time you finish the MCD, you’ve:

- Documented business rules they didn’t know they had

- Caught contradictions before code

- Made them commit to cardinalities (no backsies later)

- Identified where many-to-many relationships hide

The MCD isn’t about SQL. It’s about forcing clarity.

When a stakeholder signs off on your MCD, they’re signing off on the business logic. Not the implementation, the rules. That’s your insurance policy when they come back six months later saying “but I thought…”

You point at the MCD. You say: “We agreed on this.”

What’s next 🔗

In the next post, we’ll transform this MCD into a Logical Data Model (MLD), where we add primary keys, foreign keys, and convert those MERISE relationships with attributes (like “participates” and “is assigned”) into junction tables for implementation.

But here’s the secret: if your MCD is solid, the MLD is mechanical. It’s just applying transformation rules.

The MCD is where you win or lose the project.

-

MERISE notation basics: Entities (what exists) are rectangles, relationships (how things connect) are ovals. Both can have attributes. You’ll notice I write cardinalities like “1,n” and “0,1”, that’s minimum, maximum notation. But here’s the thing: notation doesn’t matter as long as you’re consistent and add a legend. Different methodologies use different symbols:

- MERISE:

0,11,10,n1,n - Chen ERD:

1NM - Crow’s Foot:

|o||>o>| - UML:

0..110..*1..*.

I’ve seen teams waste hours arguing about which notation is “correct”. They’re all correct. Pick one, document it, move on. What matters: Can a business person look at your diagram and understand the rules? If yes, your notation works. If they’re confused, add a legend.

Also, some standards place cardinalities at the entity they describe, others at the opposite end. Be explicit about your convention.

The goal is communication, not religious wars about ERD standards. ↩︎

- MERISE: