Thanks to Boris Novikov, who pointed me in the PAX direction in the first place and followed up with many insightful technical discussions. I’m grateful for all his time and the great conversations we’ve had—and continue to have.

I’ve been obsessed with database storage layouts for years now. Not the sexy kind of obsession, but the kind where you wake up at 3 AM thinking “wait, why are we loading 60 useless bytes into cache just to read 4 bytes?”

That’s exactly what PostgreSQL does every single day, billions of times, on production servers worldwide. And we just… accept it? No. I don’t accept it. Let me tell you about PAX.

The Library That Drives Me Crazy 🔗

Picture this: you walk into a library. Each book is a database record. PostgreSQL’s traditional storage (NSM - N-ary Storage Model) stores complete books on each shelf: chapter 1, chapter 2, chapter 3, all bound together.

Here’s the problem that keeps me up at night: when you need only chapter 3 from 1,000 books, you must pull each complete book off the shelf, flip through chapters 1 and 2 that you’ll never read, grab chapter 3, and move to the next book.

You’re wasting time. You’re wasting energy. You’re wasting cache bandwidth.

Now, columnar storage (like Parquet) says “screw it, let’s tear books apart and re-arrange them!” Put all chapter 1s on shelf A, all chapter 2s on shelf B, all chapter 3s on shelf C. Brilliant for reading chapter 3 quickly!

But here’s where it falls apart: when you need chapters 1 AND 3 from the same book, you must visit multiple shelves, collect the pieces, and reassemble the book . In database terms, that’s an expensive join operation. For OLTP workloads? Forget it. Too slow.

PAX says: keep books on the same shelf (easy reassembly), but organize chapters together within that shelf (fast sequential access).

Why NSM Makes Me Want To Scream 🔗

Let me show you the disaster we’re living with every day.

What’s Inside a PostgreSQL Page 🔗

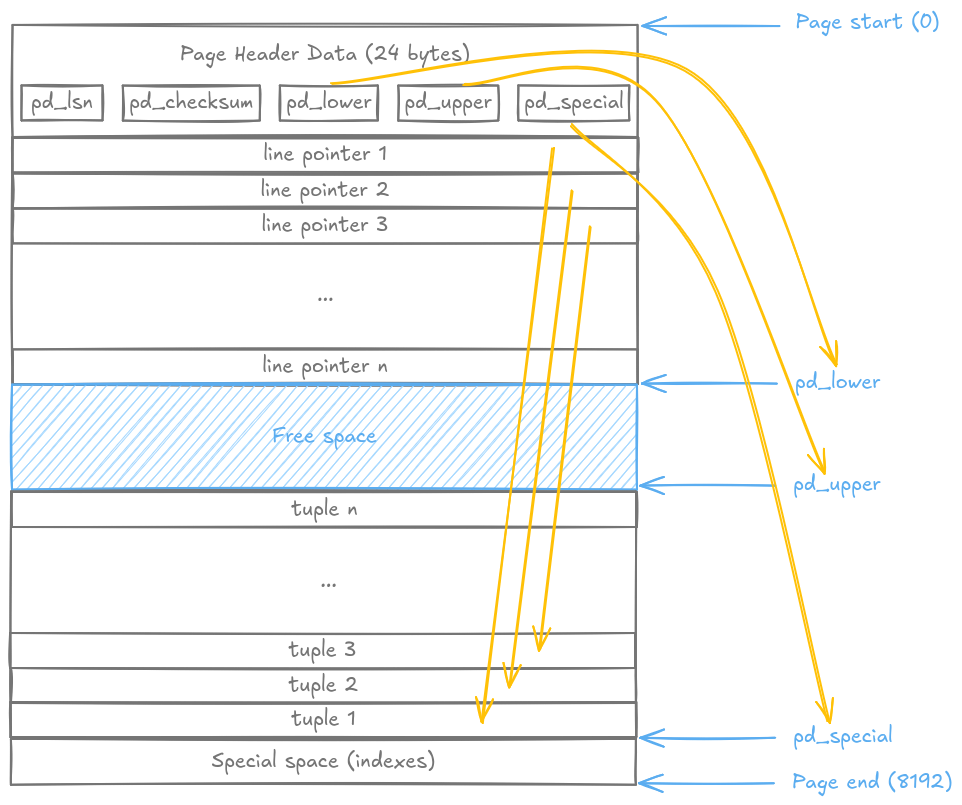

PostgreSQL stores data in 8KB pages. Here’s how a typical NSM page looks:

Note: This is a simplified view. In reality, there might be gaps between tuples (due to updates, deletes, or alignment), but the key point remains: each tuple contains all columns stored contiguously. That’s our cache problem.

The tuples grow from the bottom (pd_special), line pointers from the top (after the header), with free space in the middle. Simple, right?

Now imagine this innocent query:

SELECT age FROM users WHERE age > 30;

The Cache Catastrophe 🔗

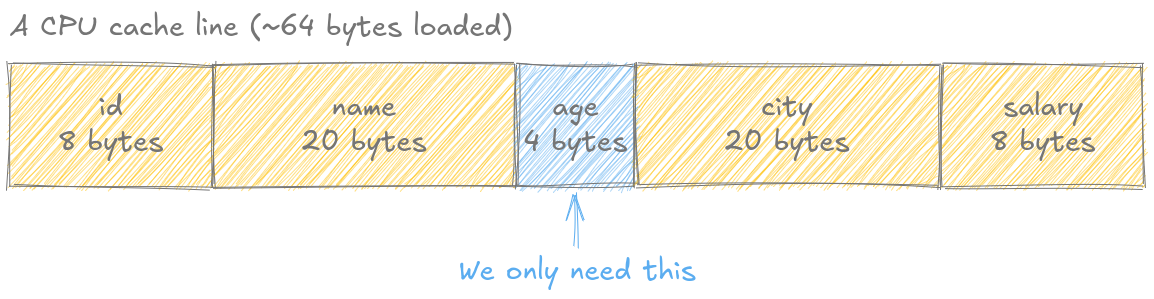

Modern CPUs don’t fetch individual bytes. They load cache lines (typically 64 bytes at a time). It’s like going to the grocery store: even if you only need milk, you’re carrying a shopping basket that holds 64 items.

When PostgreSQL reads a tuple to check the age column (4 bytes), here’s what actually loads into cache:

Note: I apologize for the crudity of this diagram. I didn’t have time to build it to scale. This shows column data only. In reality, each tuple includes a 23-byte header, making the waste even worse (83 bytes total, spanning 2 cache lines).

We wanted age. We got everything.

That’s 94% cache pollution! Ninety 👏 Four 👏 Percent 👏 (Yes, I like clapping my words, and it felt so right here, I couldn’t resist.)

On a table scan of 1 million rows:

- NSM triggers 1 million cache misses

- Useful data transferred: 4MB (just the age column)

- Wasted bandwidth: 56MB (the other columns nobody asked for)

I’ve seen DBAs play Tetris with column ordering in production—reordering datatypes to minimize padding overhead, hunting for 2-4 wasted bytes per tuple.

Meanwhile, PostgreSQL is loading 56 useless bytes per row into cache.

It’s like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Anastasia Ailamaki measured this back in 2001 on a Pentium II Xeon (yes, I’m old enough to remember those). She found 75% of cache misses were completely avoidable with PAX.

And you know what’s worse? Modern systems with 128-byte cache lines make this problem even bigger. We’re going backwards!

Enter PAX: The Solution We’ve Been Ignoring 🔗

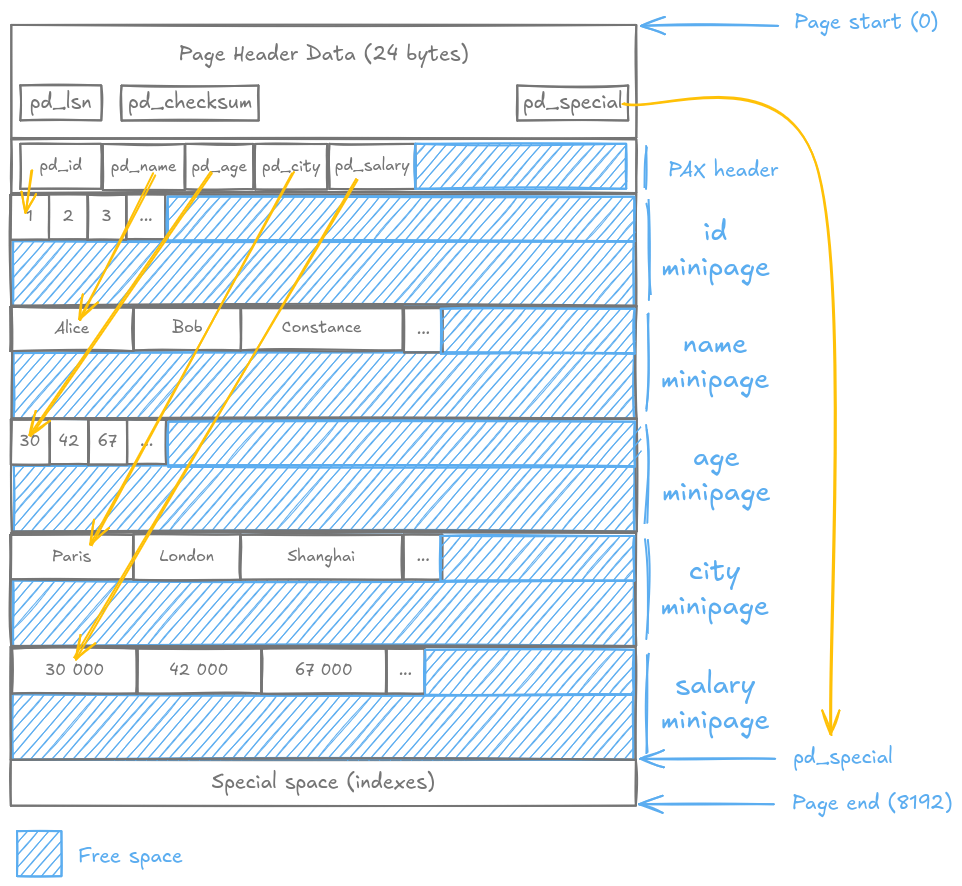

Here’s what PAX does differently. Instead of storing complete tuples, it reorganizes the inside of each 8KB page into column-oriented “minipages”:

Each minipage groups all values for one column together. The PAX header contains

offsets pointing to each minipage’s location. When you need the age column,

PostgreSQL reads only the “age” minipage, not the entire row.

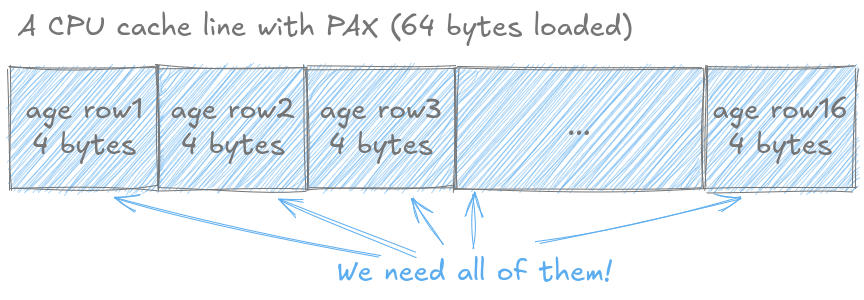

But here’s where it gets interesting. Remember that 94% cache waste we saw with NSM? Watch what happens when we query the same data with PAX:

One cache line now loads 16 age values instead of just 1. That’s not a 16% improvement—it’s a 16× improvement in cache utilization!

With NSM, scanning 100 rows for “age > 30” triggers 100 cache misses. With PAX? Only 7 cache misses (100 ÷ 16 ≈ 7). Same data, same query, 93% fewer cache misses.

This is the magic of columnar storage at the page level. PAX keeps all columns on the same page (easy tuple reconstruction), but organizes them for sequential access (cache-friendly). You get 80% of pure columnar’s benefits without the expensive cross-file joins.

PAX and Parquet: The Family Tree Nobody Talks About 🔗

Here’s something that blew my mind when I figured it out: Parquet IS based on PAX.

Parquet didn’t invent columnar storage at the page level. Anastasia Ailamaki did in 2001. Twitter and Cloudera just applied it to entire files in 2013.

The timeline:

- 2001: Ailamaki invents PAX (8KB pages in transactional DBMSs)

- 2013: Twitter/Cloudera create Parquet (PAX scaled to 128MB+ files)

So what’s the difference?

| Thing | PAX (original) | Parquet | What PostgreSQL needs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Granularity | Page (8KB) | Row group (128MB+) | Page (8KB) |

| Can you UPDATE? | Yes (MVCC) | No (files are immutable) | Yes (MVCC) |

| Where it lives | OLTP+OLAP DBMS | Data lake / batch | OLTP+OLAP DBMS |

| Fancy encoding | Not really | RLE, dict, delta, everything | Future work |

| Compression | No (in the paper) | Snappy, Gzip, Zstd | Future work |

Here’s the key insight that everyone misses: Parquet proves PAX works at massive scale, but it sacrifices mutability to get there. You can’t UPDATE a Parquet file—it’s append-only or replace-the-whole-file.

PostgreSQL needs PAX with full ACID guarantees. That means sticking with 8KB pages, keeping MVCC, and making it all work with WAL, vacuum, and the buffer manager.

PAX vs Everything Else 🔗

Let me be crystal clear about where PAX fits:

| Thing | NSM | PAX | Pure Columnar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cache locality | Terrible | Excellent | Excellent |

| Putting a record back together | Free | Cheap (same page) | Expensive (multi-file join) |

| Good for OLTP? | Yes | Pretty good | No way |

| Good for OLAP? | Not really | Pretty good | Hell yes |

| Storage overhead | Baseline | Same | Variable |

PAX gives you 80% of columnar’s benefits with 5% of the cost.

That’s the trade-off I can live with.

When You Should (And Shouldn’t) Use PAX 🔗

I’m not going to tell you PAX is a magic bullet. It’s not.

The Sweet Spot 🔗

Wide tables (12+ columns) with selective queries:

-- Perfect for PAX

SELECT event_time, revenue

FROM analytics_events -- 25 columns table

WHERE user_id = 12345;

-- Accesses 2 out of 25 columns → 92% cache savings

Mixed OLTP/OLAP workloads:

- OLTP: Single-row updates stay fast (everything’s on the same page)

- OLAP: Range scans fly (cache locality for days)

Frequent seq scans with low projectivity:

-- Nightmare for NSM, paradise for PAX

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM logs

WHERE timestamp > NOW() - INTERVAL '1 hour';

Where PAX Falls Flat 🔗

-

Narrow tables (< 8 columns): The reconstruction overhead starts to approach NSM’s simplicity. Not worth it.

-

SELECT * queries: You have to read all minipages anyway. PAX just adds overhead. but do you really need that much data? Are you sure you’re not reinventing the wheel by processing the data (even performing joins) in your applicaton ?

-

Heavy random access via indexes: Index lookup → read full tuple. Same cost as NSM. (Though index-only scans do benefit from better VM coverage.)

What Performance Gains Can You Expect? 🔗

Ailamaki measured this on a Pentium II Xeon in 2001:

- -75% data cache misses on sequential scans

- -17-25% execution time on range selections

- -11-48% on TPC-H queries (mixed joins/aggregates)

With modern hardware (DDR5, 128-byte cache lines, huge L3 caches), the absolute numbers are different, but the principles still hold. Actually, they hold even harder:

- Bigger cache lines = NSM wastes even more bandwidth

- NVMe killed I/O dominance → CPU/cache became the bottleneck

My conservative production estimate:

- OLAP queries on wide tables: 10-30% faster

- OLTP queries: 0-5% slower (minipage overhead)

- Mixed workloads: 5-15% net gain

But I want to be honest: until someone builds a POC and benchmarks it, these are educated guesses.

What’s Next? 🔗

PAX solves a real problem. The cache pollution issue isn’t going away—it’s getting worse with every CPU generation.

But here’s the thing: saying “PAX would be great” is easy. Actually implementing it in PostgreSQL? That’s where things get interesting.

Dead tuples might be challenging to manage. WAL logging can get very tricky if we don’t want to have to use full page writes each time. Vacuuming will certainly add challenges.

This is theoretical work—no POC exists yet. But I want to put these ideas out there. Maybe someone smarter than me will run with it.

Because honestly? PostgreSQL deserves better than 94% cache pollution.

References:

Ailamaki, A., DeWitt, D. J., Hill, M. D., & Skounakis, M. (2001). Weaving Relations for Cache Performance. Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (VLDB).